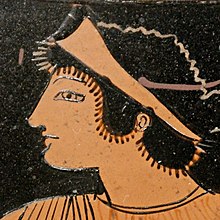

Achilles

Achilles’ most notable feat during the Trojan War was the slaying of the Trojan hero Hector outside the gates of Troy. Although the death of Achilles is not presented in the Iliad, other sources concur that he was killed near the end of the Trojan War by Paris, who shot him in the heel with an arrow. Later legends (beginning with a poem by Statius in the 1st century AD) state that Achilles was invulnerable in all of his body except for his heel. Because of his death from a small wound in the heel, the term Achilles' heel has come to mean a point of weakness in what otherwise appears to be an impregnable façade.

Thetis

When described as a Nereid in Classical myths, Thetis was the daughter of Nereus and Doris,and a granddaughter of Tethys with whom she sometimes shares characteristics. Often she seems to lead the Nereids as they attend to her tasks. Sometimes she also is identified with Metis.

Some sources argue that she was one of the earliest of deities worshipped in Archaic Greece, the oral traditions and records of which are lost. Only one written record, a fragment, exists attesting to her worship and an early Alcman hymn exists that identifies Thetis as the creator of the universe. Worship of Thetis as the goddess is documented to have persisted in some regions by historical writers such as Pausanias.

In the Trojan War cycle of myth, the wedding of Thetis and the Greek hero Peleus is one of the precipitating events in the war which also lead to the birth of their child Achilles.

History of the month's origin

'July' is for Julius

The Roman Senate named the month of July after Julius Caesar to honor him for reforming their calendar, which had degenerated into a chaotic embarrassment. Bad calculations caused the months to drift wildly across the seasons—January, for example, had begun to fall in the autumn.

The high priest in charge of the calendar, the pontifex maximus, had become so corrupt that he sometimes lengthened the year to keep certain officials in office or abbreviated it to shorten an enemy's tenure.

Effective January 1, 45 B.C.

The new calendar went into effect on the first day of January 709 A.U.C. (ab urbe condita—"from the founding of the city [Rome]")—January 1, 45 B.C.—and put an end to the arbitrary and inaccurate nature of the early Roman system. The Julian calendar became the predominant calendar throughout Europe for the next 1600 years until Pope Gregory made further reforms in 1582.

The month Julius replaced Quintilis (quintus = five)—the fifth month in the early Roman calendar, which began with March before the Julian calendar instituted January as the start of the year. Unfortunately, Caesar himself was only able to enjoy one July during his life—the very first July, in 45 B.C. The following year he was murdered on the Ides of March.

Augustus for 'August'

After Julius's grandnephew Augustus defeated Marc Antony and Cleopatra, and became emperor of Rome, the Roman Senate decided that he too should have a month named after him. The month Sextillus (sex = six) was chosen for Augustus, and the senate justified its actions in the following resolution:

Whereas the Emperor Augustus Caesar, in the month of Sextillis . . . thrice entered the city in triumph . . . and in the same month Egypt was brought under the authority of the Roman people, and in the same month an end was put to the civil wars; and whereas for these reasons the said month is, and has been, most fortunate to this empire, it is hereby decreed by the senate that the said month shall be called Augustus.

Not only did the Senate name a month after Augustus, but it decided that since Julius's month, July, had 31 days, Augustus's month should equal it: under the Julian calendar, the months alternated evenly between 30 and 31 days (with the exception of February), which made August 30 days long. So, instead of August having a mere 30 days, it was lengthened to 31, preventing anyone from claiming that Emperor Augustus was saddled with an inferior month.

To accommodate this change two other calendrical adjustments were necessary:

The extra day needed to inflate the importance of August was taken from February, which originally had 29 days (30 in a leap year), and was now reduced to 28 days (29 in a leap year).

Since the months evenly alternated between 30 and 31 days, adding the extra day to August meant that July, August, and September would all have 31 days. So to avoid three long months in a row, the lengths of the last four months were switched around, giving us 30 days in September, April, June, and November.

Among Roman rulers, only Julius and Augustus permanently had months named after them—though this wasn't for lack of trying on the part of later emperors. For a time, May was changed to Claudius and the infamous Nero instituted Neronius for April. But these changes were ephemeral, and only Julius and Augustus have had two-millenia-worth of staying power.

United States Declaration of Independence

Believe me, dear Sir: there is not in the British empire a man who more cordially loves a union with Great Britain than I do. But, by the God that made me, I will cease to exist before I yield to a connection on such terms as the British Parliament propose; and in this, I think I speak the sentiments of America.

Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

Since the American Revolution, states had divided into states that allowed and states that prohibited slavery. Slavery had been tacitly enshrined in the original Constitution through provisions such as Article I, Section 2, Clause 3, commonly known as the Three-Fifths Compromise, which detailed how each slave state's enslaved population would be factored into its total population count for the purposes of apportioning seats in the United States House of Representatives and direct taxes among the states. Though many slaves had been declared free by President Abraham Lincoln's 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, their post-war status was uncertain. On April 8, 1864, the Senate passed an amendment to abolish slavery. After one unsuccessful vote and extensive legislative maneuvering by the Lincoln administration, the House followed suit on January 31, 1865. The measure was swiftly ratified by nearly all Northern states, along with a sufficient number of border and "reconstructed" Southern states, to cause it to be adopted before the end of the year.

Preamble and Articles

of the Constitution

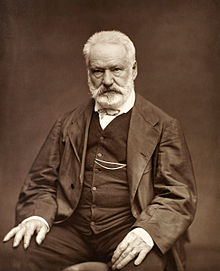

Victor Hugo

Victor Marie Hugo (;French: [viktɔʁ maʁi yɡo] ; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French poet, novelist, and dramatist of the Romantic movement. He is considered one of the greatest and best-known French writers. In France, Hugo's literary fame comes first from his poetry and then from his novels and his dramatic achievements. Among many volumes of poetry, Les Contemplations and La Légende des siècles stand high in critical esteem. Outside France, his best-known works are the novels Les Misérables, 1862, and Notre-Dame de Paris, 1831 (known in English as The Hunchback of Notre-Dame). He produced more than 4,000 drawings, and also earned respect as a campaigner for social causes such as the abolition of capital punishment.

Though a committed royalist when he was young, Hugo's views changed as the decades passed, and he became a passionate supporter of republicanism;[2] his work touches upon most of the political and social issues and the artistic trends of his time. He is buried in the Panthéon. His legacy has been honoured in many ways, including his portrait being placed on French franc banknotes.

Victor Hugo's quotes

“Music expresses that which cannot be put into words and that which cannot remain silent”

― Victor Hugo

“To put everything in balance is good, to put everything in harmony is better.”

― Victor Hugo

“What Is Love? I have met in the streets a very poor young man who was in love. His hat was old, his coat worn, the water passed through his shoes and the stars through his soul”

“People do not lack strength, they lack will.”

― Victor Hugo

“When dictatorship is a fact, revolution becomes a right.”

― Victor Hugo

Strange case of Dr.Jelly and Mr.Hyde

Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde is a novella by the Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson first published in 1886. The work is commonly known today as The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, or simply Jekyll & Hyde. It is about a London lawyer named Gabriel John Utterson who investigates strange occurrences between his old friend, Dr. Henry Jekyll, and the evil Edward Hyde. The novella's impact is such that it has become a part of the language, with the very phrase "Jekyll and Hyde" coming to mean a person who is vastly different in moral character from one situation to the next.

Dr.Jelly and Mr.Hyde

Dr. Jekyll is a "large, well-made, smooth-faced man of fifty with something of a slyish cast", who occasionally feels he is battling between the good and evil within himself, thus leading to the struggle between his dual personalities of Henry Jekyll and Edward Hyde. He has spent a great part of his life trying to repress evil urges that were not fitting for a man of his stature. He creates a serum, or potion, in an attempt to mask this hidden evil within his personality. However, in doing so, Jekyll transforms into the smaller, younger, cruel, remorseless, evil Hyde. Jekyll has many friends and has an amiable personality, but as Hyde, he becomes mysterious and violent. As time goes by, Hyde grows in power. After taking the potion repeatedly, he no longer relies upon it to unleash his inner demon, i.e., his alter ego. Eventually, Hyde grows so strong that Jekyll becomes reliant on the potion to remain conscious.

week10

inclement

inclement (adj.)

1660s, from French inclément (16c.) and directly from Latin inclementem (nominative inclemens) "harsh, unmerciful," from in- "not, opposite of, without" (see in- (1)) + clementem "mild, placid." "Limitation to weather is curious" [Weekley].

peruse

peruse (v.)

late 15c., "use up, wear out, go through," from Middle English per- "completely" (see per) + use (v.). Meaning "read carefully" is first recorded 1530s, but this could be a separate formation. Meaning "read casually" is from 19c. Related: Perused; perusing.

premonition

premonition (n.)

mid-15c., from Anglo-French premunition, Middle French premonicion, from Late Latin praemonitionem (nominative praemonitio) "a forewarning," noun of action from past participle stem of Latin praemonere "forewarn," from prae "before" (see pre-) + monere "to warn" (see monitor (n.)).

desist

desist (v.)

mid-15c., from Middle French désister (mid-14c.), from Latin desistere "to stand aside, leave off, cease," from de- "off" (see de-) + sistere "stop, come to a stand" (see assist). Related: Desisted; desisting.

recoil

recoil (n.)

c. 1300, "retreat," from Old French recul "recoil, backward movement, retreat," from reculer (see recoil (v.)). Meaning "back-kick of a firearm" is from 1570s.

recoil (v.)

early 13c. (transitive) "force back, drive back," from Old French reculer "to go back, give way, recede, retreat" (12c.), from Vulgar Latin *reculare, from Latin re- "back" (see re-) + culus "backside, bottom, fundament." Meaning "shrink back, retreat" is first recorded c. 1300; and that of "spring back" (as a gun) in 1520s. Related: Recoiled; recoiling.

pertinent

pertinent (adj.)

late 14c., from Anglo-French purtinaunt (late 13c.), Old French partenant (mid-13c.) and directly from Latin pertinentem (nominative pertinens) "pertaining," present participle of pertinere "to relate, concern" (see pertain). Related: Pertinently.

mastiff

mastiff (n.)

large, powerful breed of dog, early 14c., from Old French mastin "great cur, mastiff" (Modern French mâtin) or Provençal mastis, both from Vulgar Latin *mansuetinus "domesticated, tame," from Latin mansuetus "tame, gentle" (see mansuetude). Probably originally meaning a dog that stays in the house, thus a guard-dog or watchdog. Form in English perhaps influenced by Old French mestif "mongrel."

obsess

obsess (v.)

c. 1500, "to besiege," from Latin obsessus, past participle of obsidere "watch closely; besiege, occupy; stay, remain, abide" literally "sit opposite to," from ob "against" (see ob-) + sedere "sit" (see sedentary). Of evil spirits, "to haunt," from 1530s. Psychological sense is 20c. Related: Obsessed; obsessing.

doleful

doleful (adj.)

late 13c., with -ful, from Middle English dole "grief" (early 13c.), from Old French doel (Modern French deuil), from Late Latin dolus "grief," from Latin dolere "suffer, grieve," which is of uncertain origin. De Vaan reports that it can be derived from a PIE root *delh- "to chop" "under the assumption that 'pain' was expressed by the feeling of 'being torn apart'. A causative *dolh-eie- 'to make somebody (feel) split' could have become 'to cause pain'. The experiencer must originally have been expressed in the dative." Related: Dolefully.

wan

wan (adj.)

Old English wann "dark, dusky, lacking luster," later "leaden, pale, gray," of uncertain origin, and not found in other Germanic languages. The connecting notion is colorlessness. Perhaps related to wane. Related: Wanly; wanness.

histrionics

histrionics (n.)

"theatrics, pretense," 1820, from histrionic; also see -ics.

elusive

elusive (adj.)

1719, from Latin elus-, past participle stem of eludere "elude, frustrate" (see elude) + -ive. Related: Elusiveness.

frustrate

frustrate (v.)

mid-15c., from Latin frustratus, past participle of frustrari "to deceive, disappoint, make vain," from frustra (adv.) "in vain, in error," related to fraus "injury, harm" (see fraud). Related: Frustrated; frustrating.

symptomatic

symptomatic (adj.)

1690s, from French symptomatique or directly from Late Latin symptomaticus, from symptomat-, stem of symptoma (see symptom). General sense of "indicative (of)" is from 1751. Related: Symptomatical (1580s).

interject

interject (v.)

1570s, back-formation from interjection or else from Latin interiectus, past participle of intericere "to throw between, insert, interject." Related: Interjected; interjecting.

inert

inert (adj.)

1640s, "without inherent force, having no power to act or respond," from French inerte (16c.) or directly from Latin inertem (nominative iners) "unskilled, incompetent; inactive, helpless, weak, sluggish; worthless," used of stagnant fluids, uncultivated pastures, expressionless eyes. It is a compound of in- "without, not, opposite of" (see in- (1)) + ars (genitive artis) "skill" (see art (n.)). In chemistry, "having no active properties, neutral" (1800), specifically from 1885 of certain chemically inactive, colorless, odorless gases. Of persons or creatures, "indisposed or unable to move or act," from 1774.

salient

salient (n.)

1828, from salient (adj.).

salient (adj.)

1560s, "leaping," a heraldic term, from Latin salientem (nominative saliens), present participle of salire "to leap," from PIE root *sel- (4) "to jump" (source also of Greek hallesthai "to leap," Middle Irish saltraim "I trample," and probably Sanskrit ucchalati "rises quickly").

It was used in Middle English as an adjective meaning "leaping, skipping." The meaning "pointing outward" (preserved in military usage) is from 1680s; that of "prominent, striking" first recorded 1840, from salient point (1670s), which refers to the heart of an embryo, which seems to leap, and translates Latin punctum saliens, going back to Aristotle's writings. Hence, the "starting point" of anything.

imminent

imminent (adj.)

1520s, from Middle French imminent (14c.) and directly from Latin imminentem (nominative imminens) "overhanging; impending," present participle of imminere "to overhang, lean towards," hence "be near to," also "threaten, menace, impend, be at hand, be about to happen," from assimilated form of in- "into, in, on, upon" (see in- (2)) + -minere "jut out," which is related to mons "hill" (see mount (n.1)). Related: Imminently.

squeamish

squeamish (adj.)

late 14c., variant (with -ish) of squoymous "disdainful, fastidious" (early 14c.), from Anglo-French escoymous, which is of unknown origin. Related: Squeamishly; squeamishness.

He was somdel squaymous

Of fartyng, and of speche daungerous

[Chaucer, "Miller's Tale," c. 1386]

engrossed

engross (v.)

c. 1400, "to buy up the whole stock of" (in Anglo-French from c. 1300), from Old French en gros "in bulk, in a large quantity, at wholesale," as opposed to en detail. See gross.

Figurative sense of "absorb the whole attention" is first attested 1709. A parallel engross, meaning "to write (something) in large letters," is from Anglo-French engrosser, from Old French en gros "in large (letters)." Related: Engrossed; engrossing.

week11

inundate

inundate (v.)

1620s, back-formation from inundation, or else from Latin inundatus, past participle of inundare "to overflow, run over" (source also of Spanish inundar, French inonder). Related: Inundated; inundating.

fruitless

fruitless (adj.)

mid-14c., "unprofitable," from fruit + -less. Meaning "barren, sterile" is from 1510s. Related: Fruitlessly; fruitlessness.

poignant

poignant (adj.)

late 14c., "painful to physical or mental feeling" (of sauce, spice, wine as well as things that affect the feelings), from Old French poignant "sharp, pointed" (13c.), present participle of poindre "to prick, sting," from Latin pungere "to prick, pierce, sting," figuratively, "to vex, grieve, trouble, afflict," related to pugnus "a fist" (see pugnacious). Related: Poignantly.

The word disguises a linguistics trick-play, a double reverse. Latin pungere is from the same root as Latin pugnus "fist," and represents a metathesis of -n- and -g- that later was reversed in French.

garbled

garbled (adj.)

by 1620s of spices; by 1774 of language; past-participle adjective from garble (v.).

sanguine

sanguine (adj.)

"blood-red," late 14c. (late 12c. as a surname), from Old French sanguin (fem. sanguine), from Latin sanguineus "of blood," also "bloody, bloodthirsty," from sanguis (genitive sanguinis) "blood" (see sanguinary). Meaning "cheerful, hopeful, confident" first attested c. 1500, because these qualities were thought in medieval physiology to spring from an excess of blood as one of the four humors. Also in Middle English as a noun, "type of red cloth" (early 14c.).

phlegmatic

phlegmatic (adj.)

"cool, calm, self-possessed," and in a more pejorative sense, "cold, dull, apathetic," 1570s, from literal sense "abounding in phlegm (as a bodily humor)" (mid-14c., fleumatik), from Old French fleumatique (13c., Modern French flegmatique), from Late Latin phlegmaticus, from Greek phlegmatikos "abounding in phlegm" (see phlegm).

A verry flewmatike man is in the body lustles, heuy and slow. [John of Trevisa, translation of Bartholomew de Glanville's "De proprietatibus rerum," 1398]

corroborate

corroborate (v.)

1530s, "to give (legal) confirmation to," from Latin corroboratus, past participle of corroborare "to strengthen, invigorate," from assimilated form of com "with, together," here perhaps as "thoroughly" (see com-) + roborare "to make strong," from robur, robus "strength," (see robust).

Meaning "to strengthen by evidence, to confirm" is from 1706. Sometimes in early use the word also has its literal Latin sense, especially of medicines. Related: Corroborated; corroborating; corroborative.

comprehensive

comprehensive (adj.)

"containing much," 1610s, from French comprehénsif, from Late Latin comprehensivus, from comprehens-, past participle stem of Latin comprehendere (see comprehend). Related: Comprehensively (mid-15c.); comprehensiveness.

zealous

zealous (adj.)

"full of zeal" (in the service of a person or cause), 1520s, from Medieval Latin zelosus "full of zeal" (source of Italian zeloso, Spanish celoso), from zelus (see zeal). The sense "fervent, inspired" was earlier in English in jealous (late 14c.), which is the same word but come up through French. Related: Zealously, zealousness.

coerce

coerce (v.)

mid-15c., cohercen, from Middle French cohercer, from Latin coercere "to control, restrain, shut up together," from com- "together" (see co-) + arcere "to enclose, confine, contain, ward off," from PIE *ark- "to hold, contain, guard" (see arcane). Related: Coerced; coercing. No record of the word between late 15c. and mid-17c.; its reappearance 1650s is perhaps a back-formation from coercion.

elapse

elapse (v.)

1640s, from Middle French elapser, from Latin elapsus, past participle of elabi "slip or glide away, escape," from ex "out, out of, away" (see ex-) + labi "to slip, glide" (see lapse (n.)). The noun now corresponding to elapse is lapse, but elapse (n.) was in recent use. Related: Elapsed; elapsing.

meticulous

meticulous (adj.)

1530s, "fearful, timid," from Latin meticulosus "fearful, timid," literally "full of fear," from metus "fear, dread, apprehension, anxiety," of unknown origin. Sense of "fussy about details" is first recorded in English 1827, from French méticuleux "timorously fussy" [Fowler attributes this use in English to "literary critics"], from the Latin word. Related: Meticulosity.

domicile

domicile (n.)

mid-15c., from Middle French domicile (14c.), from Latin domicilium, perhaps from domus "house" (see domestic) + colere "to dwell" (see colony). As a verb, it is first attested 1809. Related: Domiciled; domiciliary.

lax

lax (adj.)

c. 1400, "loose" (in reference to bowels), from Latin laxus "wide, spacious, roomy," figuratively "loose, free, wide" (also used of indulgent rule and low prices), from PIE *lag-so-, suffixed form of root *(s)lēg- "to be slack, be languid" (source also of Greek legein "to leave off, stop," lagos "hare," literally "with drooping ears," lagnos "lustful, lascivious," lagaros "slack, hollow, shrunken;" Latin languere "to be faint, weary," languidis "faint, weak, dull, sluggish, languid").

In English, of rules, discipline, etc., from mid-15c. Related: Laxly; laxness. A transposed Vulgar Latin form yielded Old French lasche, French lâche. The laxists, though they formed no avowed school, were nonetheless condemned by Innocent XI in 1679.

lax (n.)

"salmon," from Old English leax (see lox). Cognate with Middle Dutch lacks, German Lachs, Danish laks, etc.; according to OED the English word was obsolete except in the north and Scotland from 17c., reintroduced in reference to Scottish or Norwegian salmon.

lax (n.)

1951 as an abbreviation of lacrosse.

sporadic

sporadic (adj.)

1680s, from Medieval Latin sporadicus "scattered," from Greek sporadikos "scattered," from sporas (genitive sporados) "scattered, dispersed," from spora "a sowing" (see spore). Originally a medical term, "occurring in scattered instances;" the meaning "happening at intervals" is first recorded 1847. Related: Sporadical (1650s); sporadically.

rash

rash (n.)

"eruption of small red spots on skin," 1709, perhaps from French rache "a sore" (Old French rasche "rash, scurf"), from Vulgar Latin *rasicare "to scrape" (also source of Old Provençal rascar, Spanish rascar "to scrape, scratch," Italian raschina "itch"), from Latin rasus "scraped," past participle of radere "to scrape" (see raze). The connecting notion would be of itching. Figurative sense of "any sudden outbreak or proliferation" first recorded 1820.

rash (adj.)

late 14c., "nimble, quick, vigorous" (early 14c. as a surname), a Scottish and northern word, perhaps from Old English -ræsc (as in ligræsc "flash of lightning") or one of its Germanic cognates, from Proto-Germanic *raskuz (source also of Middle Low German rasch, Middle Dutch rasc "quick, swift," German rasch "quick, fast"). Related to Old English horsc "quick-witted." Sense of "reckless, impetuous, heedless of consequences" is attested from c. 1500. Related: Rashly; rashness.

conjecture

conjecture (v.)

early 15c., from conjecture (n.). In Middle English also with a parallel conjecte (n.), conjecten (v.). Related: Conjectured; conjecturing.

conjecture (n.)

late 14c., "interpretation of signs and omens," from Old French conjecture "surmise, guess," or directly from Latin coniectura "conclusion, interpretation, guess, inference," literally "a casting together (of facts, etc.)," from coniectus, past participle of conicere "to throw together," from com- "together" (see com-) + iacere "to throw" (see jet (v.)). Sense of "forming of opinion without proof" is 1530s.

obviate

obviate (v.)

1590s, "to meet and do away with," from Late Latin obviatus, past participle of obviare "act contrary to, go against," from Latin obvius "that is in the way, that moves against" (see obvious). Related: Obviated; obviating.

lurid

lurid (adj.)

1650s, "pale, wan," from Latin luridus "pale yellow, ghastly, the color of bruises," a word of uncertain origin and etymology, perhaps cognate with Greek khloros "pale green, greenish-yellow" (see Chloe), or connected to Latin lividus (see livid).

It has more to do with the interplay of light and darkness than it does with color. It suggests a combination of light and gloom; "Said, e.g. of the sickly pallor of the skin in disease, or of the aspect of things when the sky is overcast" [OED]; "having the character of a light which does not show the colors of objects" [Century Dictionary]. Meaning "glowing in the darkness" is from 1727 ("of the color or appearance of dull smoky flames" - Century Dictionary]. In scientific use (1767) "of a dingy brown or yellowish-brown color" [OED]. The figurative sense of "sensational" is first attested 1850, via the notion of "ominous" (if from the flames sense) or "ghastly" (if from the older sense). Related: Luridly.

quip

quip (v.)

"make a quip," 1570s, from quip (n.). Related: Quipped; quipping.

quip (n.)

1530s, variant of quippy in same sense (1510s), perhaps from Latin quippe "indeed, of course, as you see, naturally, obviously" (used sarcastically), from quid "what" (neuter of pronoun quis "who;" see who), and compare quibble (n.)) + emphatic particle -pe.

week12

diatribe

diatribe (n.)

1640s (in Latin form in English from 1580s), "discourse, critical dissertation," from French diatribe (15c.), from Latin diatriba "learned discussion," from Greek diatribe "employment, study," in Plato, "discourse," literally "a wearing away (of time)," from dia- "away" (see dia-) + tribein "to wear, rub," from PIE root *tere- (1) "to rub, turn, twist" (see throw (v.)). Sense of "invective" is 1804, apparently from French.

inhibition

inhibition (n.)

late 14c., "formal prohibition; interdiction of legal proceedings by authority;" also, the document setting forth such a prohibition, from Old French inibicion and directly from Latin inhibitionem (nominative inhibitio) "a restraining," from past participle stem of inhibere "to hold in, hold back, keep back," from in- "in, on" (see in- (2)) + habere "to hold" (see habit (n.)). Psychological sense of "involuntary check on an expression of an impulse" is from 1876.

fortuitous

fortuitous (adj.)

1650s, from Latin fortuitus "happening by chance, casual, accidental," from forte "by chance," ablative of fors "chance" (related to fortuna; see fortune). It means "accidental, undesigned" not "fortunate." Earlier in this sense was fortuit (late 14c.), from French. Related: Fortuitously; fortuitousness.

incoherent

incoherent (adj.)

1620s, "without coherence" (of immaterial or abstract things, especially thought or language), from in- (1) "not, opposite of" + coherent. As "without physical coherence" from 1690s. Related: Incoherently.

ilk

ilk (adj.)

Old English ilca "the same" (pron.), from Proto-Germanic *ij-lik (compare German eilen), in which the first element is from the PIE demonstrative particle *i- (see yon) and the second is that in Old English -lic "form" (see like (adj.)). Of similar formation are each, which and such, but this word disappeared except in Scottish and thus did not undergo the usual southern sound changes. Phrase of that ilk implies coincidence of name and estate, as in Lundie of Lundie; it was applied usually to families, so that by c. 1790 ilk began to be used with the meaning "family," then broadening to "type, sort."

prestigious

prestigious (adj.)

1540s, "practicing illusion or magic, deceptive," from Latin praestigious "full of tricks," from praestigiae "juggler's tricks," probably altered by dissimilation from praestrigiae, from praestringere "to blind, blindfold, dazzle," from prae "before" (see pre-) + stringere "to tie or bind" (see strain (v.)). Derogatory until 19c.; meaning "having dazzling influence" is attested from 1913 (see prestige). Related: Prestigiously; prestigiousness.

placard

placard (n.)

late 15c., "formal document authenticated by an affixed seal," from Middle French placquard "official document with a large, flat seal," also "plate of armor," from Old French plaquier "to lay on, cover up, plaster over," from Middle Dutch placken "to patch (a garment), to plaster," related to Middle High German placke "patch, stain," German Placken "spot, patch." Meaning "poster" first recorded 1550s in English; this sense is in Middle French from 15c.

integral

integral (adj.)

late 15c., "of or pertaining to a whole; intrinsic, belonging as a part to a whole," from Middle French intégral (14c.), from Medieval Latin integralis "forming a whole," from Latin integer "whole" (see integer). Related: Integrally. As a noun, 1610s, from the adjective.

remuneration

remuneration (n.)

c. 1400, from Middle French remuneration and directly from Latin remunerationem (nominative remuneratio) "a repaying, recompense," noun of action from past participle stem of remunerari "to pay, reward," from re- "back" (see re-) + munerari "to give," from munus (genitive muneris) "gift, office, duty" (see municipal).

nominal

nominal (adj.)

early 15c., "pertaining to nouns," from Latin nominalis "pertaining to a name or names," from nomen (genitive nominis) "name," cognate with Old English nama (see name (n.)). Meaning "of the nature of names" (in distinction to things) is from 1610s. Meaning "being so in name only" first recorded 1620s.

expunge

expunge (v.)

c. 1600, from Latin expungere "prick out, blot out, mark (a name on a list) for deletion" by pricking dots above or below it, literally "prick out," from ex- "out" (see ex-) + pungere "to prick, pierce," related to pugnus "a fist" (see pugnacious). According to OED, taken by early lexicographers in English to "denote actual obliteration by pricking;" it adds that the sense probably was influenced by sponge (v.). Related: Expunged; expunging; expungible.

flamboyant

flamboyant (adj.)

1832, originally in reference to a 15c.-16c. architectural style with wavy, flame-like curves, from French flamboyant "flaming, wavy," present participle of flamboyer "to flame," from Old French flamboiier "to flame, flare, blaze, glow, shine" (12c.), from flambe "a flame, flame of love," from flamble, variant of flamme, from Latin flammula "little flame" (see flame (n.)). Extended sense of "showy, ornate" is from 1879. Related: Flamboyantly.

anathema

anathema (n.)

1520s, "an accursed thing," from Latin anathema "an excommunicated person; the curse of excommunication," from Ecclesiastical Greek anathema "a thing accursed," a slight variation of classical Greek anathāma, which meant merely "a thing devoted," literally "a thing set up (to the gods)," such as a votive offering in a temple, from ana "up" (see ana-) + tithenai "to put, place" (see theme).

By the time it reached Late Latin the meaning of the Greek word had progressed through "thing devoted to evil," to "thing accursed or damned." Later it was applied to persons and the Divine Curse. Meaning "act or formula of excommunicating and consigning to damnation by ecclesiastical authority" is from 1610s.

Anathema maranatha, taken as an intensified form, is held to be a misreading of I Corinthians xvi.22 where anathema is followed by Aramaic maran atha "Our Lord hath come" (see Maranatha), apparently a solemn formula of confirmation, like amen; but possibly it is a false transliteration of Hebrew mohoram atta "you are put under the ban," which would make more sense in the context. [Klein]

schism

schism (n.)

late 14c., scisme, "dissention within the church," from Old French scisme, cisme "a cleft, split" (12c.), from Church Latin schisma, from Greek skhisma (genitive skhismatos) "division, cleft," in New Testament applied metaphorically to divisions in the Church (I Corinthians xii.25), from stem of skhizein "to split" (see shed (v.)). Spelling restored 16c., but pronunciation unchanged. Often in reference to the Great Schism (1378-1417) in the Western Church.

utopia

utopia (n.)

1551, from Modern Latin Utopia, literally "nowhere," coined by Thomas More (and used as title of his book, 1516, about an imaginary island enjoying the utmost perfection in legal, social, and political systems), from Greek ou "not" + topos "place" (see topos). Extended to any perfect place by 1610s. Commonly, but incorrectly, taken as from Greek eu- "good" (see eu-) an error reinforced by the introduction of dystopia.

utopian (adj.)

1550s, with reference to More's fictional country; 1610s as "extravagantly ideal, impossibly visionary," from utopia + -an. As a noun meaning "visionary idealist" it is recorded by 1832 (also in this sense was utopiast, 1845). Utopian socialism is from 1849, originally pejorative, in reference to the Paris uprising of 1848; also a dismissive term in